Summary:

The CCCS is reviewing SP Mobility’s acquisition of ChargEco. This decision will determine if Singapore’s EV market remains competitive or becomes dominated by one operator.

While consolidation can improve efficiency, EV charging is a local business. Drivers rely on nearby chargers, so reduced competition in specific neighborhoods could lead to higher prices and lower reliability.

Maintaining multiple operators ensures better service and innovation. The CCCS must decide if this merger weakens the pressure to keep chargers functional and affordable for the public.

As the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS) deliberates on SP Mobility’s proposed acquisition of ChargEco, the stance of the decision before regulators extends far beyond a routine merger review. It will f`undamentally shape whether drivers across Singapore can reliably charge their vehicles at convenient, affordable locations—or whether they face a landscape increasingly dominated by a single operator with diminishing incentives to compete.

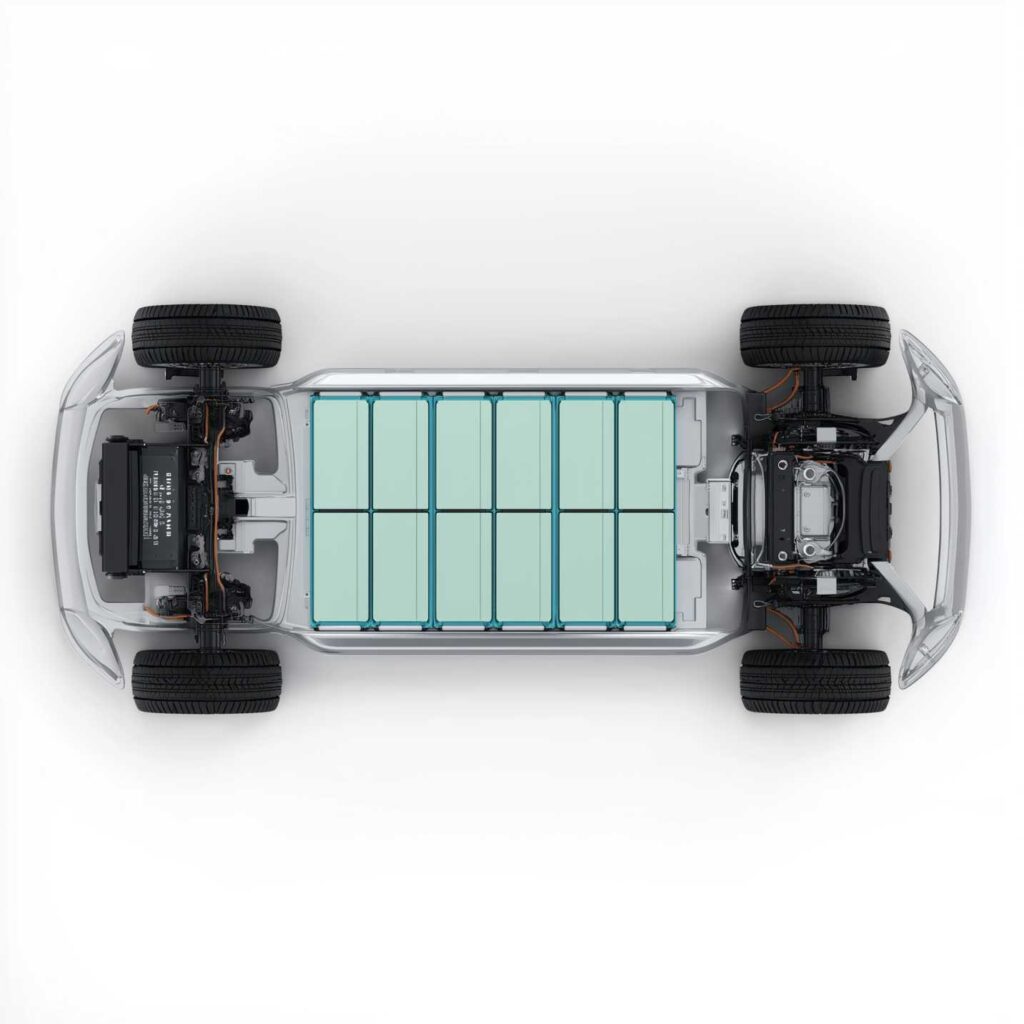

The conventional wisdom in infrastructure markets suggests that consolidation brings efficiency and scale. Larger networks, the argument goes, can invest more in technology, negotiate better rates with suppliers, and achieve economies of scale that benefit consumers. This logic has merit in many industries. But the experience of major EV charging operators globally reveals a more nuanced picture: in the charging business, scale and efficiency matter far less than local availability and operational reliability.

The Global Lesson: Network Size Is Not the Same as Network Value

Consider the competitive landscape among fast-charging operators internationally. Major networks operate thousands of chargers across multiple continents, yet pricing power and profitability remain stubbornly tied to one factor: location. Industry operators emphasize that competitive advantage flows from strategic site selection, not from network size alone. They focus on securing premium locations—highway corridors, shopping malls, office parks, residential estates—and maintaining exclusive or long-term agreements with property owners.

This emphasis on location reveals a fundamental truth about EV charging: the market is not truly national—it is intensely local. A driver in Tanjong Pagar cannot realistically use a charger in Sembawang when their car needs charging. A taxi operator based in Bedok cannot switch to a charging hub in Jurong when demand is high. The geographic constraints that make EV charging different from petrol retailing—slower charging times, longer dwell periods, and the need for convenient access—create local markets within the broader national network.

Pricing Power Through Location Control

This geographic reality translates directly into pricing power. Charging operators deploy location-based pricing strategies that reflect the simple fact that drivers in high-traffic locations have fewer alternatives. Charging costs vary dramatically by location and time of day. Membership programs create recurring revenue and customer lock-in. These mechanisms work precisely because drivers cannot easily switch to alternative networks in their neighborhoods.

The implication for Singapore is significant: even if multiple operators exist nationally, reduced competition in specific locations—residential estates, commercial hubs, workplace parking—can enable pricing that reflects local scarcity rather than competitive pressure. The CCCS’s consultation framework asks whether drivers face “low costs of switching between different CPOs.” This is an important question, but it may not fully capture the practical reality. Switching costs are less relevant if the alternative charger is kilometers away or in a different part of the island.

Operational Excellence as a Competitive Moat

Charging operators also derive competitive advantage from operational reliability and maintenance excellence—advantages that consolidation can threaten to erode. Leading operators maintain sophisticated monitoring systems, rapid-response maintenance networks, and preventive maintenance programs to minimize downtime. This operational excellence commands premium pricing and customer loyalty.

But it also requires sustained competitive pressure to maintain. In markets where competition weakens, operators face reduced incentives to invest in the infrastructure needed for high reliability and uptime. The cost of maintaining sophisticated monitoring systems, rapid-response maintenance contracts, and preventive care programs becomes harder to justify when there is no competitor threatening to capture dissatisfied customers.

For Singapore, this dynamic matters enormously. Drivers new to electric vehicles are particularly sensitive to charging reliability. A single instance of arriving at a charger to find it non-functional or occupied can shake confidence in the entire EV transition. Consolidation that reduces competitive pressure to maintain high uptime standards risks undermining consumer confidence precisely when it is most fragile.

Technology and Data: The Durable Moat

Perhaps most significant is the long-term competitive advantage that consolidation creates through technology and data. Charging operators invest heavily in proprietary software platforms, real-time diagnostics, predictive maintenance systems, and data analytics on charging patterns. These systems create advantages that are difficult for competitors to replicate.

When these capabilities are consolidated into a single operator, they become barriers to entry for future competitors. A new entrant would need to invest not just in physical chargers but in matching the incumbent’s technological sophistication and data advantages. This dynamic is particularly important in Singapore, where the government is targeting 60,000 charging points by 2030 and expects continued evolution of charging technologies and demand patterns.

The CCCS’s Challenging Task

The CCCS faces a genuinely difficult analytical problem. The consultation framework asks important questions about driver behavior, pricing, and service quality. The challenge lies in translating these questions into practical assessments of competitive impact. When the CCCS asks whether “end-customers routinely access EV charging points at various locations for convenience and are not tied down to specific charging points,” the answer likely depends heavily on where drivers live and work. For most Singapore residents, the chargers they use are not truly interchangeable with distant alternatives.

Similarly, the question of whether “numerous existing and potential competitors” exist nationally is important, but it may need to be complemented by analysis at the local level. A consolidated operator might face competition from other national networks on paper, but face no meaningful competition in the residential estates and commercial hubs where most charging actually occurs.

What the Assessment Might Consider

As the CCCS evaluates this merger, several factors may warrant particular attention:

Geographic competition patterns: Rather than assessing only national market share, it may be valuable to examine whether consolidation would reduce meaningful competition in specific high-traffic locations. If consolidation would eliminate the only competitor in key residential estates or commercial hubs, that could have significant implications for pricing and service quality in those areas.

Operational incentives: The CCCS might consider whether consolidation would affect the merged entity’s incentives to invest in reliability, uptime, and rapid maintenance response. Service quality and reliability should be treated as important competition indicators, not afterthoughts.

Technological evolution: As charging technologies continue to evolve—smart charging, vehicle-to-grid integration, demand-responsive pricing—Singapore benefits from multiple operators experimenting with different approaches. The CCCS might consider whether consolidation would reduce the diversity of technological approaches and business models in the market.

The Stakes for Singapore’s EV Transition

Public confidence in electric mobility will be shaped less by long-term government targets than by everyday charging experiences. A driver who repeatedly finds chargers occupied, non-functional, or prohibitively expensive will lose confidence in the EV transition regardless of Singapore’s 2030 or 2040 targets. A taxi operator who faces rising charging costs due to reduced competition will resist the transition to electric fleets.

The CCCS’s evaluation of the ChargEco-SP Mobility merger is one data point in a longer conversation about how Singapore’s charging infrastructure should evolve. Rather than viewing this single decision as determinative, it may be more valuable to consider how the analytical framework applied here can inform future regulatory assessments—not just of this merger, but of similar consolidation events that may occur as the EV charging market matures.

As Singapore works toward 60,000 charging points by 2030 and beyond, the industry will likely see further consolidation and strategic partnerships. Each such transaction presents an opportunity to apply the considerations outlined in this article: the importance of local competition patterns, the role of operational excellence in driving service quality, and the potential for technology and data to create durable competitive advantages.

The question before the CCCS is not whether consolidation would eliminate all competition. It is whether consolidation would weaken the competitive pressure that drives operators to maintain reliability, invest in technology, and keep prices reasonable in the specific locations where Singapore’s drivers actually charge. This is a nuanced question that deserves careful analysis—and the framework the CCCS develops in evaluating this transaction may serve as a foundation for assessing future transactions in the sector.

The consultation period closes on January 16, 2026, but the broader discussion about how to balance efficiency and competition in Singapore’s charging infrastructure should continue to evolve as the market develops.

The public consultation period for the CCCS review closes on January 16, 2026. Stakeholders—including EV drivers, fleet operators, property owners, and technology providers—are invited to submit feedback on how the proposed merger would affect competition in their local markets.